Analysis performed by AI Agent:

Over the past two decades, multiple technology and retail titans ventured into the healthcare sector, drawn by its enormous size and perceived inefficiencies. Companies like Walmart, CVS, Best Buy, Google, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, and Berkshire Hathaway (with JPMorgan Chase) all launched ambitious healthcare initiatives. These efforts ranged from opening in-store clinics to developing AI for diagnostics and even forming joint ventures to reinvent health insurance. However, most of these giants ultimately failed to capture significant market share in healthcare and scaled back their direct-care ambitions. Instead, they have largely refocused on supporting roles (e.g. providing technology or pharmacy services) rather than competing head-on with traditional healthcare providers and insurers.

This report examines each company’s foray into healthcare, their market impact, and why their direct initiatives were curtailed. It also compares these attempts to incumbent healthcare players and highlights key lessons learned.

The Allure of Healthcare and Timeline of Key Attempts

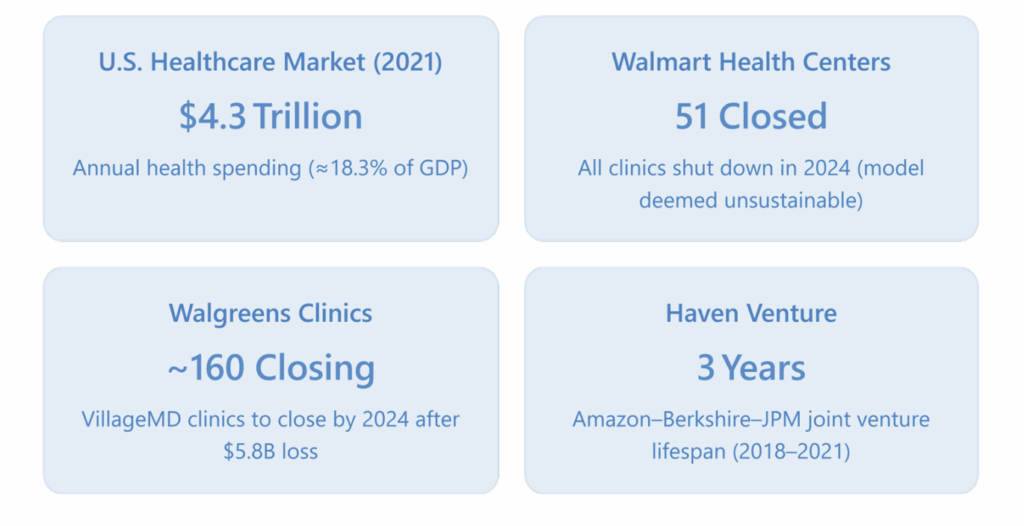

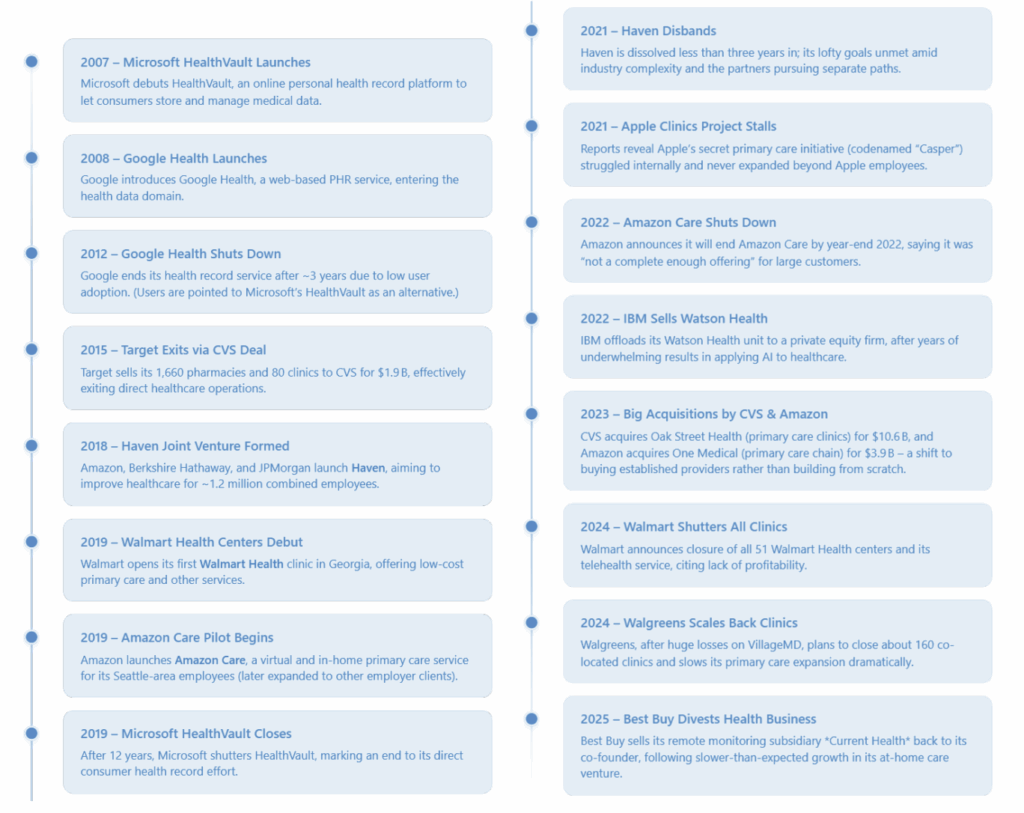

Healthcare’s massive scale – national expenditures reached $4.3 trillion in 2021 [1] (roughly $12,900 per person and 18.3% of U.S. GDP) – and its inefficiencies made it a tempting target for outside disruptors. Retail giants hoped to leverage their consumer reach to offer convenient care, and Big Tech envisioned applying data and AI to revolutionize patient services. The timeline below charts major initiatives by these companies over the last 20 years and their outcomes:

The Scorecard: Initiatives, Market Impact, and Outcomes

The table below summarizes the major healthcare forays by each company, including their initiatives, market impact or share achieved, and the outcome (whether they retreated or evolved their strategy):

| Company | Healthcare Initiatives (Years) | Market Impact / Share | Outcome (Retreat or Evolution) |

| Walmart | Walmart Health in-store clinics (2019–2024); Walmart Health Virtual Care; ongoing: pharmacies & vision centers | Opened 51 multi-service clinics across 5 states – negligible share of U.S. primary care (a few thousand visits vs. billions nationwide)2. Walmart’s 4,600 pharmacies remain significant (≈5% of U.S. prescriptions). | Exited clinics in 2024 – closed all 51 centers due to lack of profitability2. Retrenched to core retail health services (pharmacy, optical) instead of providing full primary care. |

| CVS Health | MinuteClinic retail clinics (2000s–present); acquired Aetna (insurance) 2018; HealthHUB stores; acquired Oak Street Health (primary care) 2023 | Became a top healthcare player via integration. Operates 1,100+ clinics (largest retail clinic chain). Fills \\~25% of U.S. prescriptions. Covers 24.4 million insurance members through Aetna3. 2022 revenue $322.5 B, on par with UnitedHealth’s $324 B4. (Net profit \\$4.1 B, far lower than UnitedHealth’s \\$20 B) | Transformed into an incumbent. Did not retreat; instead vertically integrated to compete broadly in healthcare. Continues expanding via acquisitions (e.g. primary care clinics) and offering insurance, pharmacy, and care services together. |

| Walgreens | In-store retail clinics (2000s–2020s); majority stake in VillageMD primary care clinics (2020–present); investments in specialty pharmacy and home care | By 2023, \\~200 Village Medical at Walgreens clinics opened – a small foothold in primary care. Core business: \\9,000 pharmacies (\\20% of U.S. Rx). VillageMD clinics had limited local market share and many underfilled patient panels. | Pulling back. After a $5.8 B goodwill write-down6, Walgreens is closing \\~160 clinics (nearly half) and slowing expansion. Remains invested in VillageMD (smaller scale) and focuses on pharmacy and partner-led health services rather than owning a huge clinic network. |

| Target | In-store pharmacies and Target Clinic (2000s–2015) | Operated pharmacies in 1,660 stores and 80 clinics, but as a mid-tier player (compared to CVS/Walgreens). Minimal share in clinics. | Exited in 2015. Sold all pharmacies & clinics to CVS for $1.9 B7. Chose to partner with CVS (which now runs those services in Target stores) rather than compete in healthcare. |

| Best Buy | Best Buy Health division (\\~2018–2025) focusing on remote monitoring and “aging in place” tech; acquisitions: GreatCall (senior devices, 2018), Current Health (hospital-at-home platform, 2021) | Provided technology for some hospital-at-home programs (e.g. ⅓ of U.S. hospital-at-home patients were monitored via Current Health platform)8. But overall a tiny share of healthcare delivery – essentially a vendor to a handful of health systems. Health segment was only a small part of $45 B Best Buy revenue. | Retreated in 2025. Sold off Current Health after growth lagged and took a $109 M charge. Pivoting back to core strengths: sell electronics and support services to healthcare providers, rather than operating a healthcare service platform itself. |

| Google Health PHR service (2008–2012); health research units (Verily, Calico); Google Fit and WearOS fitness ecosystem | Google Health PHR saw virtually no adoption beyond tech enthusiasts9. Gained 0% of personal records market (dominant players were hospital EHR portals). Broader impact mainly via Android/Wear OS devices and search data (indirect influence on health info delivery). | Service shut in 2012. Cited low usage and limited impact. Refocused on supporting roles: providing cloud services, AI, wearables, and data interoperability for healthcare providers rather than offering consumer health services directly. | |

| Microsoft | HealthVault PHR platform (2007–2019); HealthVault Insights app; Microsoft Band wearable (2014–2016) | HealthVault never gained mass uptake – few patients or providers used it, similar to Google’s experience9. No meaningful market share in health records. Some healthcare enterprises used Microsoft cloud/software, but as part of Microsoft’s general enterprise business. | Service shut in 2019. Admitted HealthVault was a failure. Pivoted to enterprise: now focuses on Azure cloud for health, AI (Nuance, etc.), and Teams for health organizations. No longer attempts direct consumer health products – instead sells tech to healthcare companies. |

| Apple | Secret primary care project “Casper” (planned 2016, tested on employees 2017–2021); consumer health features on Apple Watch & Health app (ongoing) | Casper clinics never opened to the public – limited to Apple’s own employees, so no public market share. Apple Watch, however, dominates smartwatch market (50%+ share) and is widely used for health tracking, giving Apple influence in wellness (but not actual care delivery). | Clinic plan shelved by 2021. Internal clinic project stalled amid staff departures and data concerns. Apple refocused on what works: devices and health software. It continues expanding health and fitness capabilities in Apple Watch and iPhone, partnering with healthcare providers for data integration, rather than offering medical services itself. |

| Amazon | Haven joint venture (2018–2021); Amazon Care virtual primary care (2019–2022); PillPack/Amazon Pharmacy (acq. 2018, launched 2020); Amazon Clinic telehealth (2022); acquired One Medical clinics (2023) | Before acquisitions, Amazon’s direct care reach was small. Haven served only the founders’ employees and never scaled11. Amazon Care had limited enrollment (mostly Amazon’s staff). Amazon Pharmacy has grown slowly (small share of U.S. Rx). With One Medical, Amazon now has 220+ clinics and \\~815k members – still <1% of U.S. adults. Overall, Amazon holds minimal healthcare market share so far. | Course-corrected in 2022–23. Shut down Haven and Amazon Care after concluding they weren’t working. Pivoted to acquisition: bought One Medical to stay in primary care (accepting the need for traditional clinics and doctors). Amazon continues in healthcare via One Medical, online pharmacy, and clinics, but as a hybrid approach – effectively joining the industry after initial attempts to “go it alone” failed. |

| IBM (Watson Health) | Watson Health AI platform (launched \\~2015; divested 2022) – applying Watson AI to areas like oncology, drug discovery, imaging | Despite early hype, Watson Health achieved little real-world adoption. Trials at major hospitals did not produce consistently useful results. IBM never captured noticeable market share in healthcare analytics or AI services (incumbents stuck with other vendors or in-house systems). | Exit in 2022. IBM sold Watson Health’s assets to a PE firm. CEO Arvind Krishna explained IBM lacked “the requisite vertical expertise” in healthcare. IBM refocused on horizontal AI and cloud offerings, leaving healthcare-specific solutions to companies with domain expertise. |

Sources: News reports and company statements [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11].

Retail Giants: Big Ambitions Meet Healthcare Reality

Several retail companies attempted to extend their consumer-centric business models into healthcare delivery. Their strategies often involved setting up clinics in or near their stores, offering convenience and lower prices. Here’s how each fared:

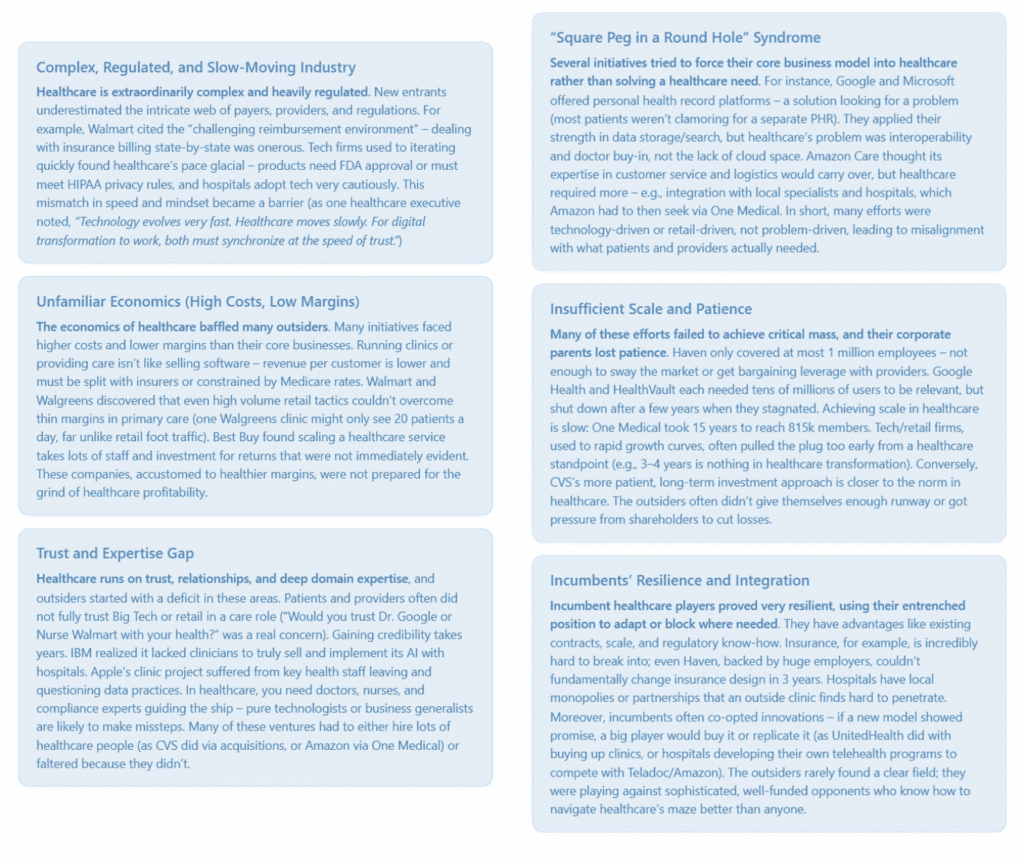

Walmart – Ambition to Retreat: “Everyday Low Price” Healthcare Faltered

Initiative: Walmart Health centers, launched in 2019, were Walmart’s bid to provide one-stop affordable healthcare. These clinics (attached to supercenters) offered primary care, dental, vision, and counseling services with transparent low pricing (e.g. $40 medical visits, $25 teeth cleanings). By 2024, Walmart had opened 51 clinics in five states 2. As the world’s largest retailer, Walmart aimed to leverage its foot traffic and cost efficiency to serve communities with limited access to care.

Market Share: Walmart’s clinics remained a niche pilot. 51 locations is a drop in the bucket relative to \\~200,000 primary care clinics nationwide. The patient volume at Walmart Health centers was modest; Walmart did not come close to denting the overall healthcare market. (For perspective, CVS MinuteClinic had over 1,100 clinics and still accounts for only a small fraction of outpatient visits.) Where Walmart does have significant presence is in pharmacy and vision: it continues to operate nearly 4,600 in-store pharmacies and 3,000 vision centers, which fill a substantial share of U.S. prescriptions and optical needs 2. But as a direct provider of medical care, Walmart’s market share was negligible – the vast majority of Americans never visited a Walmart Health center.

Outcome: In April 2024, Walmart announced it would shut down all Walmart Health centers and its telehealth service 2. This marked a dramatic reversal of its healthcare expansion. The company cited the “challenging reimbursement environment and escalating operating costs” leading to a lack of profitability that made the clinics unsustainable 2. In other words, even with cash-pay low prices, running healthcare services was more expensive than anticipated, and insurance billing was complex. The writing was on the wall when many centers weren’t meeting volume and the cost of staff (doctors, nurses) and operations eroded margins.

Walmart’s retreat was essentially admitting that healthcare doesn’t fit well into a big-box retail model. CEO Doug McMillon said the healthcare business model was “unsustainable” for Walmart at this time 4. Instead, Walmart will stick to what it knows: retail pharmacy, optical, over-the-counter health products, etc. Those services remain and even expand (e.g. Walmart is a major COVID vaccine provider). But the dream of “one-stop-shopping” including a checkup with your groceries has been put on hold. Walmart returned to its lane of supporting healthcare (as a seller of meds and glasses) rather than directly providing primary care.

CVS Health – From Drugstore to Healthcare Conglomerate

Initiative: CVS, unlike others, doubled down to become a healthcare company. Alongside its longstanding retail pharmacies and MinuteClinic (launched 2000), CVS made a bold move in 2018 by acquiring Aetna, a top health insurer, for $69 B. This vertical integration aimed to create a one-stop healthcare ecosystem: insurance + pharmacy + clinics under one umbrella. CVS also rolled out HealthHUB store formats with expanded health services and, in 2023, acquired Oak Street Health, a chain of 169 primary care clinics focusing on Medicare patients.

Market Share: Through these moves, CVS now commands a significant share of multiple healthcare segments:

- Pharmacy: CVS fills over 25% of U.S. retail prescriptions (across \\~9,900 pharmacy locations including those in Target) 9.

- Clinics: MinuteClinic, with 1,100+ locations, is the largest retail clinic provider (though retail clinics still only handle minor portions of total primary care visits).

- Insurance: Aetna brought 24 million health plan members into CVS 9. Combined with its Caremark pharmacy benefits and other services, CVS’s 2022 revenue reached $322.5 billion 9, virtually matching UnitedHealth Group’s $324 billion that year [12]. This makes CVS one of the top 2 healthcare firms by revenue. However, profitability has been thinner – CVS’s 2022 net income was $4.1 B 9, roughly one-fifth of UnitedHealth’s $20 B 9 12, reflecting the high costs of providing medical benefits.

- With Oak Street, CVS adds 160+ primary care centers (targeting 2026 for integration), which will give it deeper reach into care delivery for seniors.

Outcome: CVS is an outlier in this list – it didn’t retreat. Instead, it leveraged acquisitions to entrench itself as an incumbent. CVS’s strategy recognized that disrupting healthcare might require becoming part of it. By owning an insurer and providers, CVS can influence patient care and payment from within. The company’s vision is that a customer might get insurance from CVS (Aetna), see a doctor at a CVS clinic or affiliate, and fill prescriptions at CVS – an integrated experience.

CVS’s journey hasn’t been without challenges (integrating Aetna, ensuring clinic utilization, regulatory scrutiny), but it has fundamentally changed the company’s identity. What started as a chain of drugstores is now a healthcare conglomerate on par with Anthem or UnitedHealth. Its success so far suggests that scale and alignment are key – CVS bought the pieces needed to achieve scale (tens of millions of patients) and align incentives (insurance and providers in one entity). This was expensive and complex, but CVS’s commitment shows in how it continues to invest, e.g. paying $10.6B for Oak Street in 2023 to get more primary care capacity.

In short, CVS’s approach was to join ’em, not beat ’em: rather than breaking the healthcare system mold, CVS fused itself into the system. The result is that CVS is now often discussed in the same breath as traditional health insurers and providers, a sign that its gamble to transform itself (instead of transforming the whole industry from the outside) is paying off in influence, if not outsized profits yet.

Walgreens – Partner and Prune

Initiative: Walgreens took a slightly different path: partnership rather than outright ownership (until recently). It long provided in-store pharmacies and some clinics (via partnerships with local health systems or a smaller in-house clinic program). In 2020, Walgreens made a big bet by investing $1 B in VillageMD, a primary care startup, to open full-service doctor offices attached to Walgreens stores. It later invested more (over $5B total) to take a majority stake. The plan was ambitious: 600+ “Village Medical at Walgreens” clinics by 2025. Walgreens also acquired stakes in post-acute care (CareCentrix) and specialty pharmacy (Shields Health) as part of a health division push.

Market Share: By early 2024, Walgreens and VillageMD had opened around 200 co-located clinics [13] – a decent start but far short of the 600 goal. Those clinics gave Walgreens presence in primary care in certain markets (often serving Medicare patients with value-based care models, thanks to VillageMD’s acquisition of Summit Health). However, financially it wasn’t pretty: the healthcare segment of Walgreens was losing money. Walgreens’ core retail pharmacy still dominated its health footprint (Walgreens fills \\~819 million prescriptions annually, second only to CVS). The clinics were effectively a costly experiment with limited share – local competitors like hospitals, medical groups, or CVS’s clinics still far outnumbered them.

Outcome: Facing mounting losses, Walgreens hit the brakes. In 2023, Walgreens Boots Alliance recorded a $5.8 billion after-tax impairment charge related to its investment in VillageMD 4, acknowledging that it overpaid relative to the results. The then-CEO Roz Brewer stepped down, and the new CEO, Tim Wentworth, immediately signaled a course correction: VillageMD’s expansion needed to “go on a diet” 13. In March 2024, it was reported that Walgreens would close about 160 of the clinics (nearly half of those opened) 4 to stem losses and focus on densely populated areas only.

In effect, Walgreens is partially retreating – not abandoning the idea of primary care at retail but scaling it way back. They realized running hundreds of physician offices is capital-intensive and slower to profitability than expected. Wentworth noted many clinics struggled to fill their patient panels (i.e., attract enough regular patients) 4, which made the economics poor.

Walgreens isn’t completely out – it still owns about 30% of VillageMD, which continues to operate clinics (including the remaining Walgreens ones and standalone offices via Summit Health). But Walgreens will likely be more hands-off, letting VillageMD manage the clinical side and possibly seeking other partners to share costs. Meanwhile, Walgreens can refocus on its core: dispensing meds and leveraging partnerships like telehealth or ancillary services in-store without bearing full brunt of running doctor practices.

Key Takeaway: Even for a company already in healthcare retail, scaling up provider services proved much harder than expected. Walgreens found that just because you have real estate and brand, it doesn’t guarantee success in primary care – you need operational expertise, patient trust, payer contracts, and patience for losses. Their partial retreat underscores again that delivering care is a different game than selling products.

Best Buy – A Tech Retailer’s Home Health Experiment

Initiative: Best Buy targeted a specific niche: health technology in the home. Recognizing the trend toward telehealth and aging-in-place, Best Buy sought to use its electronics know-how and Geek Squad services to facilitate healthcare delivery at home. Key moves:

- 2018: Bought GreatCall (maker of Jitterbug senior phones and personal emergency response devices) for $800M.

- 2021: Acquired Current Health, a remote patient monitoring platform, for $400M 5.

The plan was to partner with hospital systems to help monitor patients after discharge or with chronic conditions, using Best Buy’s devices and in-home tech support. In essence, Best Buy would help health providers set up and run “hospital-at-home” programs and other telehealth initiatives.

Market Share: Best Buy Health’s revenue was not broken out fully, but it was a tiny piece of Best Buy’s \\~$46B revenue. A 2022 partnership with Atrium Health and others showed promise, and Current Health claimed to power about one-third of all U.S. hospital-at-home patients 5. That sounds high, but note: hospital-at-home was a very new, limited practice – perhaps a few thousand patients nationwide. So, in terms of overall healthcare, Best Buy’s share was negligible. It functioned as a vendor to a handful of progressive health systems. Imagine a hospital chain contracting Best Buy to deliver and set up blood pressure monitors and iPads for home patients – useful, but not industry-changing at scale (yet).

Outcome: By 2025, results were below expectations. Hospitals were cautious in rolling out home programs, partly due to uncertain reimbursement (Medicare’s hospital-at-home waiver was temporary) and their own post-pandemic financial strains. Best Buy’s CEO Corie Barry noted the at-home care business had “been harder and taken longer to develop than we initially thought” 5. The company took a $109 million restructuring charge in Q1 2025 related to its health division 5. In mid-2025, Best Buy decided to divest Current Health, selling it back to its co-founder Chris McGhee 5. Effectively, Best Buy acknowledged that while the vision was sound, it preferred a lighter model – providing tech and services without owning the entire solution.

Now, Best Buy is focusing on partnerships: for example, supplying remote monitoring kits (thermometers, pulse oximeters, etc.) and offering Geek Squad support to health providers, but not running the monitoring platform itself. It keeps a hand in the health market (because the demographics of an aging population and need for tech support are still attractive) but has stepped back from being a platform owner.

Reflection: Best Buy’s story is a reminder that healthcare moves at a slower pace than tech investors might like. A great concept (hospital-at-home) still depends on regulatory shifts and provider adoption, which are slow. A retailer’s quarterly-driven mindset can clash with that. Best Buy choosing to retreat and refocus suggests they’d rather earn steady income as a supplier than gamble on a long-term transformation of care delivery.

Target – Knowing Your Limits

Initiative: Target’s approach was more limited from the outset. It offered pharmacies and small in-store clinics as an add-on convenience for shoppers. By 2015, Target had 1,660 pharmacies and 80 Target Clinics in its stores 3. But Target lacked vertical integration (no insurance or PBM) and was essentially playing catch-up to CVS/Walgreens in pharmacy.

Outcome: Target leadership realized that being a distant third in pharmacy wasn’t worth the effort, and running clinics wasn’t core to their brand. In June 2015, Target struck a deal for CVS to acquire and operate all Target’s pharmacies and clinics 3. For $1.9B, Target handed off that entire business. This move allowed Target to focus on retail merchandising (its strength) while still offering guests a pharmacy service (now run by CVS).

By exiting early (and profitably), Target avoided the pitfalls others later faced. It didn’t sink years of investment into healthcare with uncertain returns. Instead, it effectively outsourced healthcare in its stores to an expert. Now every Target pharmacy is branded CVS, and it’s CVS’s headache to manage those operations.

Insight: Target exhibited a rare strategic discipline, recognizing that not every growth idea fits their model. The sale to CVS was essentially an admission that “this is better handled by a healthcare specialist.” It’s a contrast to Walmart, which tried to DIY health services for a few years longer. Sometimes quitting while ahead is a wise choice – Target’s retail business thrived in subsequent years without the distraction of a subscale health unit.

Tech Giants: Moonshots and Missteps in Healthcare

The big technology companies – Google, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, IBM – all undertook high-profile healthcare initiatives, banking on their innovation prowess. The results, by and large, were humbling. Each faced unique challenges, but common threads emerged around low adoption, regulatory hurdles, and the importance of domain knowledge. Here’s a closer look:

Google – Data Powerhouse Finds Healthcare Tough to Crack

Initiative: Google’s most direct play was Google Health (launched 2008), a personal health record website intended to centralize people’s medical info (lab results, prescriptions, conditions) in one Google-managed profile. Google also pursued health through other arms: Verily (life sciences research, like glucose-sensing contact lenses), Calico (longevity research), and later integrated health tracking in Android (Google Fit) and wearables (Fitbit acquisition in 2021). But Google Health was the emblematic attempt to engage consumers and providers in a new way.

Market Impact: Minimal. Google Health never gained momentum. Many patients never even heard of it; those who tried it often found it didn’t do much. Hospitals and doctors did not partner widely with Google on it, so the data available was limited (some pharmacy records and a few clinics’ data, but not the major EHR systems). By Google’s own admission, it failed to catch on broadly 6. Outside Google Health, the company’s influence on healthcare has been indirect – via Android’s dominance (lots of health apps exist on Android phones, but that’s not Google delivering care) and Google Search (people asking health questions). In terms of actual healthcare services market share, Google essentially had none.

Outcome: Google shut down Google Health in January 2012, declaring it hadn’t achieved the scale or impact desired 6. The service lasted less than 4 years. Reasons were dissected in the media: lack of widespread adoption by consumers, reluctance of healthcare providers to cooperate, and possibly Google’s insufficient understanding of healthcare workflows 6. After this, Google pivoted to a different strategy:

- It focused on enabling others: Google Cloud for healthcare (hosting data, AI tools for health analytics), APIs for health app developers, and open-source projects like the FHIR protocol for data interoperability.

- It also put more effort into wearables and tracking (buying Fitbit, introducing Google Health Connect to aggregate fitness data) – aligning with consumer tech it knows, rather than medical records.

- Google tried a second wind by forming a Google Health division in 2018 under Dr. David Feinberg, aiming to coordinate health projects across the company, but that too was reorganized in 2021, with projects distributed to other units.

Today, Google is definitely present in healthcare, but mostly behind the scenes. You won’t see “Google Hospital”, but hospitals might use Google’s AI to detect disease in scans, researchers might use Google Cloud for genomic data, and millions use Android Wear devices to count steps. Google learned that direct disruption (especially in sensitive health data management) was harder than anticipated, so it shifted to a role of tech provider and data aggregator – which aligns better with Google’s strengths.

Microsoft – Early Entry, Early Exit, and a Refocus on Enterprise

Initiative: Microsoft was a pioneer with HealthVault, launched in 2007 (a year before Google Health). HealthVault allowed individuals to store health information on a Microsoft-run platform and share it with providers or apps. Microsoft also developed Amalga (software for health systems) and invested in health intelligence solutions. Additionally, it entered wearables briefly with the Microsoft Band, and created health bots and AI prototypes.

Market Impact: HealthVault, like Google Health, failed to become mainstream. It survived longer (until 2019) but never achieved broad consumer adoption or provider integration 6. A telling anecdote: when Google Health shut in 2012, Google actually suggested users move their data to HealthVault 6, implying HealthVault was the last of its kind standing – yet even with that, it didn’t grow much. Hospitals were entrenched with their own electronic record systems and didn’t interface deeply with HealthVault. Consumers found little value in manually uploading data. Microsoft’s wearables and other consumer health efforts were minor blips (the Band was discontinued in 2016; it wasn’t a major player like Apple Watch or Fitbit).

Where Microsoft did (and does) have impact is selling technology to healthcare organizations – for example, many health systems use Office 365, Azure cloud, or now Teams for telemedicine. But that’s as a vendor of horizontal tech, not the specific health solutions it initially envisioned.

Outcome: In April 2019, Microsoft announced it would shut down HealthVault on November 20, 2019 6, effectively conceding that its direct consumer health experiment was over. The company explicitly framed it as a shift of strategy: “the end of HealthVault is an admission of failure for Microsoft’s initial forays into health”, but Microsoft was refocusing “toward the enterprise market” in healthcare 6. That same year, Microsoft poured energy into its Azure healthcare cloud and a partnership with Walgreens (which didn’t end up bearing much fruit on Walgreens’ side, but signaled Microsoft’s focus on B2B).

By 2022, Microsoft doubled down by acquiring Nuance Communications (for ~$20B) – a leader in clinical speech recognition (Dragon Medical) – to bolster its healthcare cloud offerings with AI documentation tools. Now, Microsoft’s health efforts are all about empowering hospital systems, clinics, and insurers with cloud, AI, and collaboration software. It’s a far cry from HealthVault’s consumer-centric vision, but it’s a space where Microsoft is finding success (Azure is a top cloud choice in healthcare, and Teams is used for virtual visits and care coordination).

In summary, Microsoft learned that trying to directly change consumer behavior or patient records was outside its wheelhouse. Instead, it realized its core competency – software infrastructure – could be applied to healthcare if it worked with the incumbents. This “if you can’t beat ’em, sell to ’em” approach has made Microsoft a quiet power in health IT without needing to brand itself as a healthcare company to the public.

Apple – The Most Personal Device, but Not Your Doctor

Initiative: Apple’s public narrative in health has been about devices: the iPhone’s Health app (2014) and especially the Apple Watch (from 2015 onward), which has increasingly sophisticated health sensors (heart rate, ECG, blood oxygen). These have made Apple a major player in digital health and personal fitness. However, behind the scenes, Apple once contemplated going much further. Around 2016, Apple started project “Casper” – an ambitious plan to provide primary care services directly. They even opened two quiet Apple employee clinics near Cupertino and hired Dr. Sumbul Desai from Stanford to lead the effort 7. The concept was that Apple, using data from Watch and iPhone, plus elegant software, could deliver superior primary care and eventually offer it to consumers as a subscription.

Market Impact: Apple’s direct healthcare services never materialized for the public. The employee clinics served as a testbed but apparently did not yield a breakthrough model that Apple felt ready to scale. So, Apple has 0% market share in healthcare delivery outside its workforce. That said, Apple has been enormously impactful in consumer health tech: the Apple Watch is credited with potentially saving lives by detecting heart problems; HealthKit/Health Records on iPhone allows patients of hundreds of hospitals to view their medical records on their phone 6 (over 140 health systems by 2019 6). Apple has effectively become a de facto health accessory provider for millions – but always emphasizing it’s not practicing medicine, just providing tools.

Outcome: By mid-2021, signs emerged that Apple’s grander healthcare plans had stalled. A Wall Street Journal investigation in June 2021 revealed internal turmoil: the primary care project encountered staff departures, data integrity questions, and cultural clashes between the Apple way and healthcare norms 7. Some employees were concerned that Apple was collecting clinic data in a “haphazard” way, and the engagement in the internal health app (HealthHabit) was low 7. The project Casper did not progress to expansion, and Apple did not announce any consumer clinic service. Instead, Apple issued statements highlighting the success of its device-based health initiatives (like how Apple Watch has led to new health research, etc.), implicitly downplaying any notion it wanted to be a healthcare provider.

So, Apple quietly sidelined its primary care ambitions. Dr. Desai’s team refocused on things like new Watch features and the Apple Heart and Movement Study (with Apple devices contributing data). Essentially, Apple realized its strength is in platforms and hardware that integrate with healthcare, not running clinics or insurance.

There’s an oft-cited line that Apple CEO Tim Cook wants health to be Apple’s lasting legacy. That may be true in terms of impact – the proliferation of health tracking and empowering individuals – but notably, Apple decided that doesn’t mean running hospitals or clinics. Apple’s approach now is to keep enhancing the health capabilities of its products, secure user health data on-device, and collaborate with the existing healthcare system (e.g. Apple’s Health Records feature connects with Epic systems at hospitals). It will let doctors remain responsible for care, while Apple provides the devices and software to support that care.

Amazon – Still Searching for the Right Cure

Initiative: Amazon made multiple high-profile moves:

- Haven (2018): A joint venture with Berkshire and JPMorgan aimed at employee healthcare innovation. This had the attention of the whole industry (Warren Buffett calling healthcare a “tapeworm” on the economy).

- Amazon Care (2019): A virtual primary care service (with telemedicine and home nurse visits) initially for Amazon employees, later serving a few corporate clients. It was Amazon’s own healthcare service brand.

- Pharmacy: Acquisition of PillPack in 2018 led to Amazon Pharmacy in 2020, delivering prescription meds nationwide, aiming to undercut or compete with retail pharmacies.

- One Medical (2023): Acquisition of a national primary care group with 220+ clinics for $3.9B – a massive step acknowledging the need for brick-and-mortar presence.

- Various other experiments: Amazon Alexa health skills, an Amazon Halo fitness band (launched 2020, discontinued 2023), and Amazon Clinic (2022) for text-based consults on minor issues.

Market Impact: Prior to One Medical, Amazon’s direct impact was modest:

- Haven: Only ever piloted a few small projects (like a new insurance plan for some JPMorgan workers) and never scaled beyond the founding companies. It didn’t touch the general public at all 10.

- Amazon Care: At its peak, served Amazon employees in several states and signed up a handful of external companies (reports mention Hilton and Whole Foods). It wasn’t adopted by large numbers; by 2022 it was clear uptake was lackluster.

- Pharmacy: Amazon Pharmacy gained some customers, especially during the pandemic, but incumbents like CVS and Walgreens still fill the vast majority of prescriptions. Amazon’s share is estimated in the low single digits.

- One Medical: Post-acquisition, Amazon has ~815,000 One Medical members. That is a significant patient base for primary care in certain cities, but nationally it’s a sliver (~0.3% of Americans). It’s a foothold that can grow, though.

Amazon’s influence is also felt in how competitors responded (e.g., drug chains beefing up mail delivery and insurers buying providers in anticipation of Amazon’s moves). And AWS is a major cloud provider in healthcare, though that’s Amazon as infrastructure, not health services.

Outcome: Amazon’s path has been iterative:

- Haven’s failure (2021): Haven disbanded after 3 years with no major successes 10. The venture’s end was widely seen as proof that even giants combined couldn’t easily fix healthcare. Each partner started doing their own thing (e.g., JPMorgan partnered with Cigna, Berkshire’s companies pursued different wellness programs, and Amazon… went its own way as we see).

- Amazon Care’s shutdown (2022): In August 2022, Amazon announced it would close Amazon Care. In an internal memo, the executive in charge said “Amazon Care… is not a complete enough offering for the large enterprise customers… and wasn’t going to work long-term.” 8 This frank assessment showed Amazon recognized pure virtual primary care wasn’t sufficient; employers wanted more comprehensive solutions (like physical clinics or specialist networks).

- Acquisition pivot: Almost simultaneously, Amazon had agreed to buy One Medical, which has on-the-ground clinics and a tech-enabled primary care model. This indicated Amazon decided to invest big and buy expertise rather than build slowly. By mid-2023, One Medical was part of Amazon.

- Continuing Investment: In 2023, Amazon also closed a $3.9B deal for One Medical, and has kept Amazon Pharmacy and Amazon Clinic running. It laid off some staff in its Amazon Health Services as part of broader cuts, signaling a drive for efficiency and realistic scaling.

So where are we now? Amazon is still in the healthcare game, arguably more deeply than any other Big Tech, but it has changed tactics. It no longer thinks it can do it purely “the Amazon way” (fast, virtual, disrupt everything). Instead, it bought a company that operates very much like a traditional provider (just with nicer clinics and an app).

The question is whether Amazon can use its customer-centric ethos and logistical prowess to make One Medical a stronger competitor in primary care, or integrate Pharmacy to offer a smooth experience (e.g., prescribe at One Medical, fulfill at Amazon Pharmacy). That’s the current experiment. It’s too early to judge success, but clearly Amazon didn’t walk away entirely as others did – it still sees a huge opportunity worth chasing, albeit with a humbler approach that acknowledges healthcare’s brick-and-mortar and human elements.

IBM Watson Health – AI Hype Hits Hard Reality

Initiative: IBM’s Watson, famously victorious on Jeopardy! in 2011, was heralded as a new era of AI. IBM quickly directed Watson at healthcare, hoping to revolutionize diagnosis and treatment decisions. Watson Health was formed around 2014 and IBM spent over $4B acquiring companies (Merge for imaging, Truven for data, Phytel for population health, Explorys for analytics) to feed the Watson engine. The marquee application was Watson for Oncology, co-developed with Memorial Sloan Kettering, to help doctors choose cancer treatments. IBM also targeted pharma (Watson for Drug Discovery) and payers.

Market Impact: In practice, Watson often underdelivered:

- Some partner hospitals found Watson for Oncology wasn’t very useful or even recommended unsafe treatments in certain cases, due to training on limited data [14].

- The AI’s advantages over traditional analytics never clearly materialized. In areas like radiology AI, independent startups moved faster than IBM.

- By late 2010s, news stories described Watson Health as struggling to meet revenue targets and losing key clients. MD Anderson Cancer Center famously canceled a Watson project after spending millions with little to show.

- Watson Health did have some ongoing customers (e.g., certain health systems using its imaging analytics), but it did not become an indispensable tool in healthcare. Competing AI solutions from Google, smaller startups, or those built by provider organizations themselves were often chosen over Watson.

Outcome: In January 2022, IBM sold the core data and analytics assets of Watson Health to Francisco Partners (a PE firm) for around $1B 11. Effectively, IBM dismantled Watson Health, keeping the Watson brand for other non-health AI products. In June 2022, IBM’s CEO Arvind Krishna explained the sale: IBM lacked “the requisite vertical expertise” in healthcare, and decided that industries like healthcare need specialized players 11. He said, “Verticals should belong to people who have… domain expertise, \\[who] have credibility in that vertical… healthcare companies, people in medical devices… have credibility to carry out AI in depth” 11. This was a candid admission that IBM, for all its tech talent, didn’t have the doctors, the intimate knowledge of healthcare’s complexities, or the salesforce relationships to succeed in selling AI to providers. Also, he noted IBM prefers “horizontal” tech (like AI that any industry can use) as its focus 11.

Post-divestiture, IBM has turned to what it calls “Watsonx”, a general AI platform, and left it to the buyer (now rebranded as Merative) to figure out how to monetize Watson Health’s pieces in healthcare.

Downfall reasons: Watson Health encapsulates how AI in healthcare is not plug-and-play. The algorithms must be trained on extensive high-quality medical data and fit into clinical workflows. Without enough real-world data or understanding of how doctors make decisions, Watson stumbled. Additionally, selling to hospitals is notoriously slow; IBM’s traditional clients are CIOs for IT systems, not clinical leaders – a mismatch when trying to sell a tool doctors must trust. IBM learned the hard way that you can’t just “disrupt” healthcare with AI unless you also master the healthcare side of the equation.

Traditional Incumbents Still Rule the Market

Despite all these well-funded attempts from outside players, the established healthcare companies – insurers, hospitals, physician groups, pharma – still overwhelmingly control the market. Consider the landscape:

- Insurance and Benefits: The largest health insurer, UnitedHealth Group, not only had revenues of $324B in 2022 12, but also earned about $20B in profit 12 (far beyond any new entrant’s health venture). United’s Optum unit owns physician practices, urgent cares, and surgery centers, employing around 60,000 physicians and delivering care to millions 14. CVS’s Aetna and other big insurers (Anthem, Cigna, Humana) also maintain tens of millions of members. No tech or retail firm made a dent in insurance enrollment (even Haven never offered a health plan beyond internal pilots).

- Providers: Hospital systems like HCA (180+ hospitals) or Ascension (2,600 sites of care) and large medical groups still see the vast majority of patients. For primary care, companies like Optum, Medicare-focused groups like ChenMed or Oak Street (now CVS), and traditional independent practices dominate. The newcomers’ clinics – Walmart’s 51, Amazon’s 220 via One Medical, Walgreens/VillageMD \\~200 – are a tiny fraction of outpatient care locations.

- Pharmacy: CVS and Walgreens remain the go-to for most Americans. Amazon Pharmacy is growing slowly, and while it may carve a niche, it has not significantly eroded the incumbents’ share yet. (One analysis noted that even if Amazon captures 10% of the pharmacy market in coming years, CVS and Walgreens would still have around half between them.)

- Healthcare IT: Electronic health record (EHR) systems are dominated by Epic, Cerner (Oracle), and a few others. Google and Microsoft learned that getting patients or doctors onto a new platform (like Google Health or HealthVault) was nearly impossible when Epic and similar systems are so entrenched in clinical workflows.

In essence, the core conduits of healthcare dollars and patient flow remain in the hands of those who have been doing it for decades. Even an innovator like Apple, with all its consumer reach, ended up partnering with incumbents (e.g. making Apple Health Records work with hospital EHRs, rather than replacing them).

Competitive response: It’s worth noting that the threat (or hype) of disruption likely spurred incumbents to improve:

- Insurers like UnitedHealth and Humana invested heavily in data analytics, digital apps, and customer experience, partially inspired by Big Tech’s focus on user-friendly design.

- Pharmacies responded to Amazon by offering same-day delivery, expanding 90-day mail order, and pushing their own digital apps. Walgreens partnered with FedEx for home delivery soon after Amazon Pharmacy launched.

- Hospitals and traditional providers highlighted their strengths – human care and trust – something tech companies lack, and doubled down on integrating digital tools in a physician-directed way.

Additionally, some incumbents simply bought up potential disruptors (as when Aetna, a 150-year-old insurer, was acquired by CVS, or when UnitedHealth’s Optum bought up digital health startups and physician groups). This co-optation means a lot of “disruption” got absorbed into the existing system.

The net effect is that, as of today, the health system looks largely the same structurally. Patients still get insurance from insurers, see doctors at clinics or virtually through those providers, get meds from pharmacies, and occasionally use tech-enabled enhancements (like a telehealth video, a smartphone ECG, or an AI-driven radiology scan) – but usually provided by or in partnership with the traditional players. Big Tech and retail’s logos aren’t front and center in most care experiences (with small exceptions, like seeing One Medical | Amazon on a clinic door, or using an Apple Watch heart alert to prompt a doctor visit).

Why Did These Initiatives Struggle? Key Challenges and Lessons

Looking across all these efforts, common challenges emerged that unraveled many of them. Healthcare proved to be unlike any industry these companies had tackled. Here are the key reasons, distilled:

These challenges led to the common outcome: retreat or reinvention of strategy. It’s striking that nearly all these companies eventually said, in one form or another, “We learned a lot about healthcare and are refocusing our efforts differently now.” In PR speak, they didn’t call it failure, but that’s effectively what happened for the initial bold plans.

Conclusion: Disruption Deferred – Collaboration is the New Mantra

In 2015, one might have predicted that by 2025 we’d all be getting healthcare from an Apple clinic, a Google AI, or an Amazon doctor. That hasn’t happened. Healthcare has proven to be a tougher nut to crack than industries like retail, media, or travel that tech companies transformed. The experiences of these giants illustrate that real, systemic disruption in healthcare is a long game, likely requiring partnership with the very incumbents one set out to disrupt.

A few key takeaways from this 20-year saga:

- Underestimating Healthcare is Costly: Almost every company initially thought they could apply their successful formula to healthcare and succeed quickly. They discovered healthcare has its own rules and gravity. “Move fast and break things” doesn’t work when broken things can mean lives at risk. Most had to slow down or exit and acknowledge limits.

- Success Came When They Joined the System: CVS succeeded by becoming an insurer and provider – basically becoming a healthcare company. Amazon’s renewed push (One Medical) is essentially joining the establishment (running clinics that bill insurance) rather than inventing a new system. Big tech like Microsoft found success providing technology to the healthcare industry, not replacing it. The pattern is clear: working with and inside the system has been more fruitful than trying to overthrow it.

- Incremental Change vs. Revolution: While none of these efforts individually “revolutionized” healthcare, collectively they nudged it. We now expect more convenience (retail clinics, telehealth), price transparency is improving (in part due to pressures from players like Walmart and regulatory changes), and digital health is mainstream (thanks to Apple, Google, etc.). The change has been incremental and the incumbents implemented much of it – but the outside pressure helped catalyze that.

- Healthcare’s Future – Hybrid Models: The next phase seems to be hybrid models. Amazon’s clinic+virtual+pharmacy concept, CVS’s insurer+retail clinics, or Best Buy’s tech+partner approach show a blending of new and old. The most effective interventions might be those that respect healthcare’s complexities but use tech and retail savvy to improve experiences and efficiency.

At this point, we can say that the major tech and retail entrants did not conquer healthcare – but they’ve influenced it, and they aren’t giving up entirely. Healthcare is simply too large (now over $4 trillion a year) and important to ignore. They are recalibrating. Instead of dreams of “disrupting healthcare like Uber disrupted taxis,” the talk is now about collaboration, integration, and slow innovation with an eye on trust and compliance.

Perhaps the grand “disruption” will come in some form eventually – maybe new entrants will target specific niches (like AI diagnostics or home care) and quietly reshape them, or maybe one of the giants will find a formula that clicks. But the lesson so far is humility. As Michael Dalton of MetroHealth aptly said, the key is moving at the speed of trust: these companies will have to earn trust step by step, working alongside doctors and nurses, to truly make inroads. Trust, more than tech prowess or capital, has proven to be the currency that matters most in healthcare.

Citations: The analysis above references information from credible sources including press releases, news articles, and industry reports 2 4 10 6 7 8 11 9 5 3, which are indicated throughout the text. These sources document the rise and fall of the initiatives discussed, providing evidence for the outcomes and insights noted.

Trust, more than tech prowess or capital, has proven to be the currency that matters most in healthcare.

[1]National health spending reached $4.3 trillion in 2021

[2]Walmart to close health centers due to ‘lack of profitability’

[3]CVS to Acquire and Run Target’s Pharmacies in 7.9B Deal

[4]Walgreens Suffers $6 Billion Loss As VillageMD Clinic … – Forbes

[5]Best Buy Sells Current Health Back To Co-Founder, Former CEO

[6]Microsoft HealthVault is officially shutting down in November

[7]Apple’s healthcare push stalled by employee departures

[8]Internal memo: Amazon Care to shut down, ‘not a complete enough …

[9]CVS reports double-digit revenue growth in 2022, $4.1B in profit

[10]Haven, the Amazon-Berkshire-JPMorgan venture to disrupt health … – CNBC

[11]IBM CEO explains why company offloaded Watson Health

[12]UnitedHealth Group Reports 2022 Results

[13]Walgreens Shutters 160 VillageMD Clinics after $6 Billion Loss

[14]UnitedHealth, flush off 2022 momentum, eyes membership, value-based …